If you aren’t sure about what vaccinations your horse needs, when they should be given and how often, then Horse & Hound’s definitive guide contains everything you need to know

There are a number of vaccinations for horses available to help protect your horse’s health. These include equine flu, tetanus, equine herpes virus (EHV) and equine rotavirus and strangles. Unfortunately a 2019 field trial of a vaccine to protect against grass sickness proved inconclusive.

Vaccinations for horses: Equine flu | Tetanus | Strangles | Equine herpes virus | Equine rotavirus | Reactions | Vet’s view

Only healthy horses should be vaccinated. If your horse is showing any signs of being unwell, discuss this with your vet prior to any vaccine being given. It is recommended that a horse is given a couple of quiet days after being vaccinated, with only light work and turnout. A horse should not be worked hard or made to sweat as they may be feeling below par or a little sore at the site of the injection.

A small percentage of horses experience a reaction after being vaccinated. If your horse appears unwell then speak to your vet for advice. If your horse has previously had a reaction then discuss it with the vet prior to any future vaccinations being given.

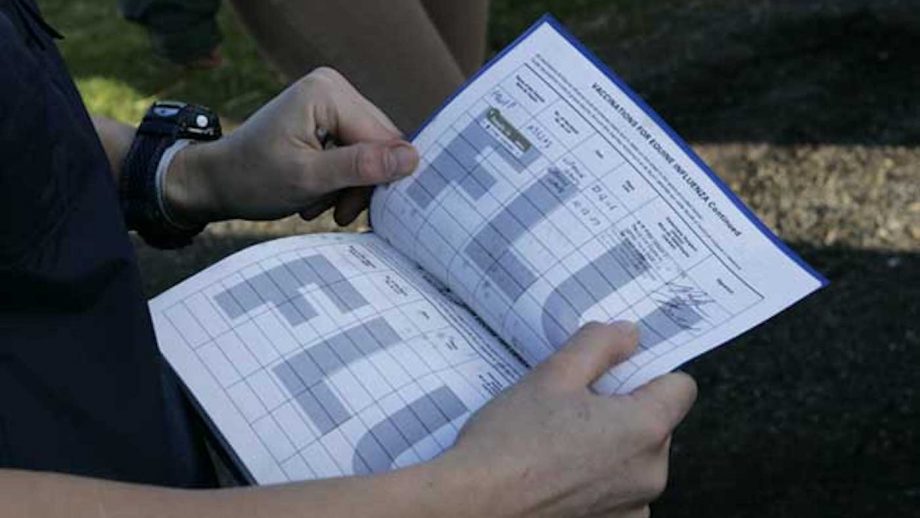

All vaccination records should be kept up to date in the horse’s passport document.

What vaccinations does a horse need?

The most common vaccinations given to horses in the UK are for equine flu and tetanus. Equine flu vaccination is compulsory for horses competing in affiliated competitions and is recommended for all horses. Breeding stock should also be vaccinated for equine herpes virus.

How often does a horse need vaccinations?

Most governing bodies of equestrian sports require annual equine flu vaccinations after the initial course is completed. The FEI requires more frequent boosters. It is advised that owners of leisure horses also arrange yearly boosters.

Vaccines against tetanus are typically given to horses every other year.

The primary vaccination course for equine herpes virus in non-pregnant horses involves two vaccinations four to six weeks apart, followed by booster vaccines every six months. Pregnant mares are typically vaccinated at five, seven and nine months of gestation to reduce the risk of abortion associated with EHV.

Why you should vaccinate your horse?

“Equine vaccinations are important to prevent your horse from contracting nasty diseases, particularly contagious diseases such as equine flu,” explains Wolverhampton vet Sue Taylor.

“Horse owners often say that their horse doesn’t go anywhere and so doesn’t need to be vaccinated, but if your horse is on a stable yard alongside horses who do compete, there is a chance that those competition horses could bring back a virus.

“Herd immunity is a concept that owners should be aware of too. If there is a yard full of vaccinated horses, it provides a kind of ‘wall’ to flu and other viruses. It can’t pass on very successfully as vaccinated horses limit the amount of virus that is shed. Whereas if your horse is unvaccinated, they’ll catch it and snot virulent virus all over the place, making it more likely to be caught by other horses — even vaccinated horses can present with mild signs. The higher the vaccination percentage in the overall population, the less opportunities there are to infect horses.

“Also, owners of competition horses should be aware that an up-to-date vaccination record is a requirement of many sporting governing bodies for horses competing under their rules.”

Every horse should be vaccinated against equine flu.

Equine flu (influenza) vaccination for horses

What is equine flu?

Influenza is a viral infection that affects the respiratory system resulting in a high fever, runny nose and coughing. Though rarely fatal, it can be a very debilitating disease that can take a considerable amount of time for horses to recover from. A major outbreak occurred in the UK during 2019 mainly affected unvaccinated animals, although some vaccinated horses also showed clinical signs.

Which horses need a flu vaccination?

Every horse should be vaccinated against equine flu. It is a requirement for competition horses to have up-to-date protection under the rules of most governing bodies.

Equine flu vaccination schedule

The first one is typically given around five months old, second one about four weeks later (21-60 days), then again around six months (120-180 days), followed by an annual booster. If you miss the window for these vaccinations or an annual booster, you will likely have to start the course again to comply with affiliated competition rules (check the rules of your governing body).

British Dressage, British Showjumping, British Eventing and British Riding Clubs require annual boosters. Horses competing under FEI rules must have been vaccinated within six months, plus up to 21 days, of a competition, but cannot have been vaccinated within seven days of arriving at a competition venue.

The flu vaccine is the only one that the FEI insists all horses taking part in international competitions have. From 1 January 2026, flu vaccinations must be recorded digitally in the FEI HorseApp, as well as in the horse’s passport. Vets must enter the vaccination details on the day it is administered. There is a transition period running until 30 June 2026 during which no sanctions will be issued, but from 1 July 2026 missing or incorrect digital records may result in fines.

The British Horseracing Authority’s windows between the first, second and third vaccines are 21-60 days, then 120-180 days, followed by six monthly boosters. In all cases, horses should not attend competitions within seven days of receiving a vaccine.

Other relevant info

Only healthy horses should be vaccinated for flu. If your horse has a temperature, cough or is unwell in any way, make your vet aware before he vaccinates your horse with flu, as the vaccine could make him more ill.

Tetanus vaccination for horses

What is tetanus?

Tetanus is caused by the production of endotoxins by the bacteria Clostridium tetani and is often fatal in horses. The spores of the bacteria are found in soil and enters the tissues via wounds. Deep puncture wounds are particularly dangerous as they provide an ideal site for infection.

Which horses need the tetanus vaccination?

Every horse is susceptible to tetanus due to the nature of the disease.

Tetanus vaccination schedule

A primary course of two vaccinations given four to six weeks apart, followed by a booster 12 months later. Subsequent vaccinations can be given at two yearly intervals. Foals will receive antibodies from their mother’s colostrum, but many are also given tetanus anti-toxin shortly after birth too.

Vaccination for tetanus is usually started at five months old and is often given as a combination vaccine with equine flu.

Other relevant info

You can get lumps or unwell horses occasionally after vaccination, but it is usually from a combined flu/tetanus vaccination rather than a sole tetanus injection.

Equine herpes virus (EHV) vaccination for horses

What is equine herpes virus?

There are five types of equine herpes virus, but EHV-1 and EHV-4 are the most clinically important and they are the only types that can be vaccinated against. EHV-1 and EHV-4 can cause a flu-like respiratory infection in horses, but may also cause abortion in pregnant mares and severe neurological disease. The effectiveness of the EHV vaccine against the neurological form of the disease is unclear.

Which horses need an EHV vaccine?

Any horse can have the herpes vaccine, but it is particularly important for breeding mares — many big studs will insist a mare is vaccinated before being allowed to foal there.

EHV vaccination schedule

The first vaccine can be given at five months old with the second vaccine at four to six weeks later, followed by a booster every six months. To provide effective immunity against abortion caused by EHV-1 and EHV-4 a course of three vaccinations should be given to a mare during her fifth, seventh and ninth months of pregnancy.

Other relevant info

There is a lot of virus shed in the aborted foetus’s fluid so surrounding mares can potentially catch the disease from breathing in the virus. The vaccine doesn’t always prevent the mare from aborting, but it can limit the amount of the virus that she passes when giving birth.

Equine rotavirus vaccination for horses

Pregnant mares are vaccinated against equine rotavirus to protect their foals from suffering diarrhoea or illness caused by the virus. Vaccines are given in the eighth, ninth, and 10th months of pregnancy in order that the antibodies can be transferred to the foal via the mare’s colostrum (first milk). Please contact your vet for more information.

New strangles vaccine

In 2004, a strangles vaccine called Equilis StrepE was launched, but unfortunately, three years later, it was withdrawn due to “quality control issues”.

Over a decade later, and a new protein-based strangles vaccine Strangvac has been developed by a group of scientists from the Animal Health Trust (AHT), the Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, the Karolinska Institute and Intervacc AB, to prevent equines from contracting the highly contagious disease.

Trials were carried out on 16 horses, 13 of which were protected from strangles after being given the vaccine, and none showed signs of adverse reactions. The vaccine was made available to vets in the UK in 2022.

Strangles is caused by a bacteria called Streptococcus equi, which causes large pus-filled abscesses in a horse’s throat and neck. An estimated 600 outbreaks of strangles occur each year in the UK alone, so the development of the new vaccine will benefit horse health world-wide. Please contact your vet for more information.

Reactions to vaccines

“Some horses can have a reaction to their vaccination,” says Sue Taylor. “In some cases it is the injection itself that causes the reaction, not the vaccine. Vets shouldn’t swab the area of the vaccine injection because there is a risk that the antiseptic can deactivate the virus. If you have a very dirty horse, there is the risk that the needle will take bacteria in with it, causing an infection and abscess.

“I usually inject vaccines into the brisket (chest) which is often a cleaner part of the horse and if they do react, it drains well. A lot of people inject in the neck but if the horse reacts, it is a difficult area for the fluid to drain from, and the horse can find it difficult to put its neck down to eat and drink, and certainly can’t be ridden.

“If you have a very hairy horse, it might be advisable to clip a patch of hair with clippers or scissors to minimise the risk of dirt being taken in with the needle, or ensure the horse is clean in the area he is being injected.

“If they have a history of reactions, speak to your vet about placing the injection in his chest, and discuss the vaccine itself. In some cases, it is the carrier of the vaccine that causes a reaction, although this is much less likely now with modern vaccine technology. If you know that your horse is prone to reacting to a certain vaccine, tell your vet so that he can organise an alternative next time.”

Additional reporting by Stephanie Bateman

- For unlimited access to advice on how best to care for your horse, subscribe to the Horse & Hound website

You might also be interested in:

Equine flu: what all owners need to know to protect their horses

Equine herpes virus – all you need to know right now

Strangles: what is it, how to spot the signs, plus a new vaccine to help protect your horse

Tetanus in horses: what every owner needs to know

Subscribe to Horse & Hound magazine today – and enjoy unlimited website access all year round

Horse & Hound magazine, out every Thursday, is packed with all the latest news and reports, as well as interviews, specials, nostalgia, vet and training advice. Find how you can enjoy the magazine delivered to your door every week, plus options to upgrade your subscription to access our online service that brings you breaking news and reports as well as other benefits.