The Tokyo Olympics dressage is over, our extensive magazine reports have gone to press and I’ve finally had a chance to reflect on the competition as a whole, and the fresh new Olympic dressage format.

At first glance, the new format, while designed with an aim of helping make dressage more accessible, appeared anything but – I found it difficult to get my head around, even with an extra year in which to do so.

But once I had grasped the concept, I actually found I quite liked the new structure to the competition – especially in an Olympics context.

There are undoubtedly flaws and glitches in the format, for example the fact that it was hard for some riders to gauge on which day they might ride the grand prix. With the start list not released until after the trot-up on the day before the competition began, this meant it was tricky to make and effectively execute preparation plans, and this is something I hope will be looked at again.

But overall, I found the competition structure refreshing and interesting, and it undoubtedly made for a superb sporting event.

To break it down a little further, here are what I consider to be the three biggest changes this year, and my thoughts on each…

1, Three to a team

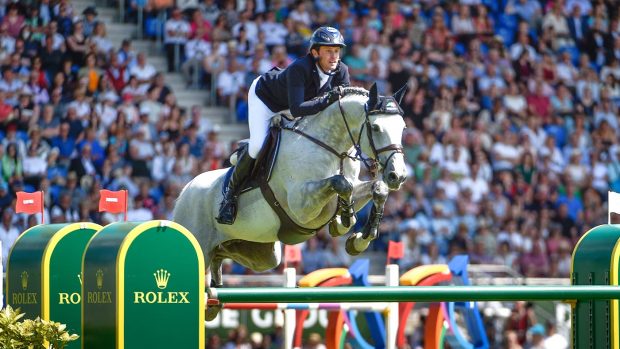

This was certainly controversial, and one made across the board in equestrian sport. In dressage, there is less chance of a rider suffering a true car crash of a round compared to eventing or showjumping, but instead the tiniest error can make a big difference.

Riders definitely felt significant pressure, and Carl Hester described not having a drop score as “terrifying”. But very few combinations performed notably worse in the special than they did in the grand prix, suggesting that perhaps the pressure was not having an undue effect on the majority of performances. Did some people ride more conservatively, aiming for a safe clear rather than a sparkling test? Perhaps, but those that finished on the podium certainly gave it everything they had, and were duly rewarded.

For me, it certainly made it easier to keep track of the team standings as we moved through the final, without having to account for one rider’s score being dropped from each team, and I think that is an important aspect of the sport becoming easier to understand for those less familiar with it.

2, The special to decide the team medals

The grand prix acted only as a qualifier and the special was the sole test that decided the team medals. I have thought long and hard about my feelings on this. The special is a technically harder test that is not as commonly seen in competition as the grand prix and so I do think it is appropriate for it to be the key test at the Olympic Games.

I also much prefer the special being part of the the team competition than running as an individual class, as at European championships and World Equestrian Games, in addition to the freestyle. For me, one set of team medals and one set of individuals medals makes perfect, simple sense.

Dressage purists might point out that the special doesn’t include two movements considered key classical tests for horse and rider: the rein-back and the canter zig-zag. This is true, but of course every competitor has had to qualify for the special by performing these two movements well enough in the preceding grand prix.

With no drop score, I have mixed feelings about only one test deciding the result, rather than combination of grand prix and special scores as at previous Olympics. It it worth noting that, had these Olympics been run under the same format as in Rio, Britain would have taken a decisive team silver over the USA – all three USA riders under-performed in the grand prix compared to the special, while two of the three British riders had better scores in the grand prix, which of course did not count under the new format.

It would be easy for me to say that on this basis, I would have preferred combined scores to decide medals. However, while I wouldn’t be upset if the structure did revert back to this at future Olympics, I’m not going to be bitter. Just as in other sports, this format demanded athletes to produce their best in one single performance, a final, and that does seem appropriate at an Olympics. The pressure, of course, is immense, especially with an animal added to the mix, but at least in dressage, compared to say, the 100m final, there are lots of movements in which to earn marks – in many sports that come down to one crucial performance, that moment is over in seconds.

3, Riding in groups

This was the element of the Olympic dressage format that seemed to confuse people the most. The 60 riders in the grand prix were split into six groups, distributed according to world ranking to ensure that the top riders were spread across the groups.

I may be in the minority here, but I like this, especially for an Olympics. The concept of heats is a very familiar one in other sports, and I don’t why it shouldn’t be the case in dressage. I liked that there was at least one top 10 ranked rider in each group, and while some groups were inevitably more competitive than others, it meant the competition reached six climaxes, rather than edging steadily towards one big peak at the end.

It may have also helped the judges to stay consistent, rather than becoming inadvertently more generous with their marks as the competition progresses, as can often be the case.

I felt that the top two riders from each heat progressing automatically to the freestyle followed by the six best “lucky losers” also worked well on this occasion because it was indeed the top 18 that qualified – and I was pleased to have predicted 15 of them correctly in advance. However, there’s no guarantee that this would be the case. Using world rankings aims to alleviate this, but we all know that seeding systems in other sports can throw up wildly unexpected results.

That said, I don’t think the potential for a worthy pair to be denied the chance to ride the freestyle is any worse than under the old format, whereby only three riders from each team of four can compete in the freestyle. This often denies members of top teams, who may have been the lowest scorer from their nation but still finished high up the leaderboard overall, from contesting the individual medals.

So, what’s the verdict on the Olympic dressage format?

Opinions on the format vary wildly, and many people will have come away from this Olympics still without full understanding of it. But I like the tension and excitement that this format brought, as well as its consistency with other Olympics sports – it is arguably an easier concept for a general sports fan to understand than for pure dressage followers.

Equestrians as a rule don’t tend to think very favourably towards big change. But if we want our wonderful sport to prosper in the wider sporting world, change is something we should at least be open to.

You might also be interested in…

Bluffer’s guide to dressage at the Tokyo Olympics

Horse & Hound’s dressage editor explains the main changes and what they mean for the format of the dressage competition...

Germany win Olympic gold in Tokyo, while Britain claim bronze, USA silver

A new Olympic champion is crowned – how Jessica von Bredow-Werndl won gold in Tokyo

Who will qualify for the Tokyo Olympics grand prix freestyle? H&H’s dressage editor makes her predictions…

Subscribe to Horse & Hound magazine today – and enjoy unlimited website access all year round

Horse & Hound magazine, out every Thursday, is packed with all the latest news and reports, as well as interviews, specials, nostalgia, vet and training advice. Find how you can enjoy the magazine delivered to your door every week, plus options to upgrade your subscription to access our online service that brings you breaking news and reports as well as other benefits.