Allergic skin disease can be severe and debilitating. Intense itching can cause distress to the horse and result in self-mutilation, potentially leading to compromised welfare. In many cases it results in a lifelong problem requiring ongoing management.

With continued research our understanding is increasing and allergic skin disease is gaining greater recognition as an important condition in horses. Despite many similarities with other species, however, our knowledge of the issue is still lacking. There is a definite need for improved methods of diagnosis and management.

System alert

An allergy is an overreaction of the immune system to a normally harmless substance.

A large number of allergen-specific antibodies are produced, which, in turn, stimulate the release of substances such as histamine into the body. These substances cause inflammation that can result in localised skin reactions, including swelling, itching or hives. More severe reaction — anaphylactic shock, for example — can involve the circulatory or respiratory systems.

Allergic diseases can be triggered by many things, including insect bites, substances in feed, environmental allergens (such as dust, pollen or mould), drugs, or substances that come into contact with the horse (such as plants, shampoo and fly spray).

The development of a clinical allergy depends on multiple factors, among which are genetic predisposition and environmental exposure. The immune status of the individual horse and any previous episodes of sensitisation also play their part.

For many years it was thought that an allergic horse developed antibodies against an allergen, while a non-allergic horse did not. Through ongoing research, it is now known that the processes involved are not that simple. Allergen-specific antibodies can also exist in clinically healthy, non-allergic horses.

It has been established that an imbalance of the immune system, combined with reduced regulatory function, plays a fundamental role in the development of allergies. It is not just the presence of the allergen-specific antibody that causes the allergy, therefore, but the way in which the horse’s immune system responds.

The term “atopy” is used to describe a heritable condition in which the horse is predisposed to develop allergies to multiple different environmental allergens. Characteristics of allergic skin disease include itching (pruritus), recurrent hives (urticarial reactions), patchy hair loss and small lumps or crusting. Onset of clinical disease tends to occur at about three to four years of age.

Disease is often suspected, based on history and clinical signs. Factors such as distribution of lesions or time of year may raise suspicions.

Often, diagnosis is made based on clinical signs alone. Similar clinical signs can be produced by other diseases, however, so diagnostic tests are typically performed to rule out other more common skin conditions (for example lice or other skin parasites) before progressing to allergy testing. These tests can include microscopic examination of the hair or top layer of skin, bacterial or fungal culture, and the use of skin biopsies.

What’s that itch?

Allergy testing is performed to confirm clinical diagnosis and to identify the trigger factors responsible for the allergy.

Sometimes the trigger is obvious, such as new bedding or fly spray, or a recently adminstered medication. In less clear-cut cases, testing would be performed to try and identify the causative allergen. A management plan aimed at allergen avoidance and desensitisation to the trigger is then key to successful treatment.

Allergy testing can be performed using either intradermal testing or serum allergy testing. There is some scientific evidence to support intradermal testing, but very little for serum testing.

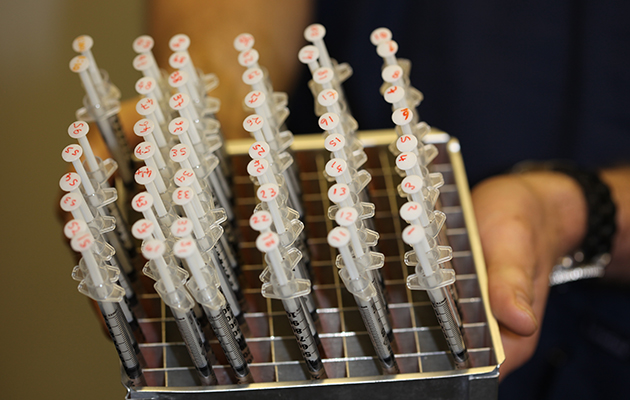

Intradermal allergen testing (IDAT) has been used in horses for more than 20 years and is considered the “gold standard” for identifying allergens of potential importance. The horse is sedated before a large patch of hair is clipped from his neck and multiple potential allergens are injected into his skin in tiny amounts. These injection sites are then examined for signs that one or more of the allergens have produced an allergic response.

The panel of potential allergens used is based upon various triggers, including common plants and trees, mites (house dust, for example, or forage mites) and certain insects such as the Culicoides midge, which is associated with sweet itch.

Allergic horses tend to show multiple positive reactions, some of which are unlikely to be causing the clinical disease. So although testing can be useful, identifying the allergens that are true causes can be challenging.

The results of the test can be used to develop immunotherapy injections tailored to the horse’s specific allergies. With repeated injections the horse becomes less sensitive to the triggers. It has been reported that 60% of owners using immunotherapy were able to discontinue giving other medications to their horses, such as antihistamines or steroids.

As IDAT can be expensive to set up and requires experience to interpret the results, it is typically offered only at specialist referral practices. It can take several hours to complete and medication must be discontinued prior to testing.

Serological allergen testing is a blood test to measure allergen-specific antibodies that have been produced by the horse. It is a popular option due to its simplicity, convenience and widespread availability.

Although straightforward in principle, allergen blood tests perform poorly in practice. Tests can often give incorrect positives and results have poor repeatability. The unreliability of currently available blood tests significantly limits their use in the diagnosis of allergic disease.

Research targets

The list of potential allergens to which a horse could react is extensive and in reality is immeasurable.

Commercially available tests have allergen panels designed to identify the most common allergies, so are by no means absolute. Furthermore, most test preparations include crude allergen extracts which are not equine specific and can lead to false positive results.

Most of what is currently known comes from studies in other species. Ongoing research is focused on developing more reliable equine-specific diagnostics as well as vaccination strategies to prevent and manage disease, with insect bite hypersensitivity continuing as a key area of interest.

Other studies have focused on the investigation of specific biochemical markers, such as fat molecules, and it has been suggested that these may have an active role in the course of equine allergies. It is hoped that this research will lead to more effective tools to aid the diagnosis and treatment of allergic skin disease in the foreseeable future.

Ref Horse & Hound; 30 March 2017