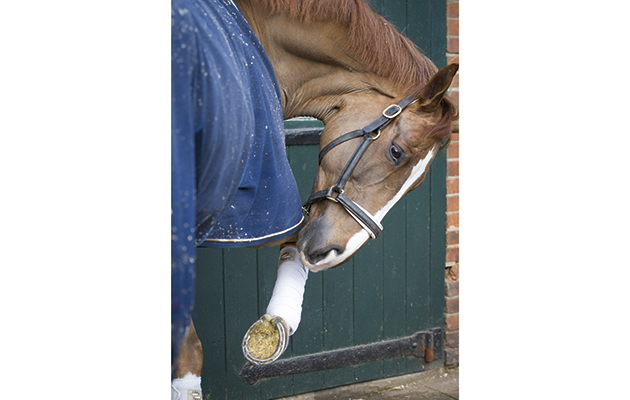

Paralympic dressage rider Ricky Balshaw’s top ride LJT Engaards Solitaire (pictured top) was a serial door-kicker.

At dinnertime in particular, the gelding (known as Sid) loved to bash the stable door with a foreleg. Eventually this made him lame.

“In 2014 he bruised a cannon bone from kicking the door,” says Ricky. “Because he kept repeating the behaviour, it didn’t heal. He ended up having a year off to recover.”

Time off for injury is never ideal, but when the injury is caused by a habit that isn’t easily rectified, the issue becomes problematic.

Ricky’s first port of call was Simon Woods MRCVS, director of Fyrnwy Equine Clinic in Shropshire.

“Sid presented with lameness of the left foreleg,” Simon explains. “The lameness was a lot worse when he was ridden. We nerve-blocked and isolated the region, but there wasn’t much to see on X-ray or ultrasound. So he had an MRI scan at the Animal Health Trust in Newmarket, which revealed bruising to the front and inside of the lower cannon bone.”

Sid was put on box rest for six weeks and given a drug that inhibits the activity of the cells that break down bone. This allowed the cells to build up again and proliferate.

“The bone needed to rest and settle,” adds Simon. “Bone is constantly being turned over, with cells breaking down and creating new bone — a recycle process — to repair the damaged area.

“After six weeks, Sid was sound and we could begin rehabilitation work. Stopping the habit and preventing reinjury was a big part of this process. Sid’s routine was managed to prevent him wanting to kick the door, so he was fed first at feed time and his door was padded.”

Pinpointing the cause

“Horses may kick the stable door for a number of reasons, but it is often a sign of anxiety or stress,” says equine behaviour expert Justine Harrison. “It usually begins as the horse is frustrated by being confined, so he paws the ground at the door because he wants to go out or knows that his feed is on its way.

“If a horse is rewarded for performing a behaviour, he is likely to repeat it,” she adds. “For example, someone on the yard may try to stop the noise by giving him a haynet, turning him out or just paying him attention — this can even come in the form of a reprimand or shouting.

“In the horse’s mind, his behaviour has been reinforced, so he will repeat it to see if it has the same result. The person inadvertently reinforces the behaviour again and the process becomes a vicious circle.”

How does door-banging compare to a stereotypical behaviour?

“It differs because humans are a bit to blame,” says Simon. “Horses that door-bang have learnt to associate the behaviour with getting attention or feed, while wind-sucking or crib-biting are often associated with pain and stress-release due to boredom or gastric ulcers.”

Serious injury from kicking the door is rare, adds Simon.

“If you can stop the horse from banging, the prognosis is generally very good,” he says. “The main problems tend to be caused by high-impact traumas from the foreleg hitting something vertical, which causes bruising and oedema (swelling) within the bone. Bone-bruising from door-kicking is not the same as a concussion or splint injury, because these are both caused by loading trauma being sent up the leg from the ground rather than a direct hit on the bone surface.

“In Sid’s case, we weren’t that worried about joint injury because of the location of the bruising. If a horse bangs the knee specifically, however, damaging the front margin of the joint, this could cause articular (joint) damage and further problems.”

Seeking solutions

Door-kicking can be an extremely difficult habit to stop once established. Ricky’s first aim was to reduce the risk of injury.

“Sid’s stable is now like a padded cell,” he says. “We’ve also changed his routine and management so he gets fed and turned out first, to limit the behaviour.”

Removing the door completely is another option. By using a stall chain across the doorway, the horse has nothing to bang against.

Justine believes that breaking the habit requires a management rethink.

“The best solution is not to stable the horse, especially at the time he would perform the behaviour,” she says. “A change of environment can help, such as a different stable with plenty to occupy him.

“If it happens at feed time, change his routine, give him something to distract him while his feed is being prepared or feed him in a different place. Provide a choice of forages and stable toys and ensure he always has access to equine company.

“Trying to stop the horse performing the behaviour in the moment is risky at best, and can be detrimental to his welfare,” adds Justine. “There are devices available that punish the behaviour with sprays, while some owners try to deaden the sound by attaching mats to the door. These techniques may help in some cases but actually make matters worse in others, as the horse often works harder to achieve the same effect.

“Even if these techniques work temporarily, the original reason for the behaviour has not been addressed,” Justine says. “He may well perform another behaviour to reduce his stress.”

Hoofing it

Other limb-related behaviours include:

Wall-kicking

“Kicking out with the hindlegs is often associated with gastric ulcers, but it can also be caused by horses being stabled too close together or next to horses they don’t like,” explains Simon. “This can sometimes predispose the horse to pedal bone fractures in the hind feet as they traumatise themselves against the stable walls.”

Stamping

Repeated stamping of the forelegs is often associated with irritation caused by unwelcome guests.

“We’d look for mites, particularly in a heavy cob-type with feathers,” says Simon. “The injury caused would be more concussion-based.”

Pawing

“When a horse is trapped in a stressful situation, his first instinct is to escape,” says Justine. “If he can’t he will often fidget — performing a ‘displacement behaviour’ such as shaking his head or pawing a leg.

“By moving his body in this way, he is attempting to reduce stress and cope better in the situation. Displacements are natural behaviours performed in an unusual context. They’re seen commonly but are often overlooked and misunderstood.”

Ref: Horse & Hound; 9 June 2016